p

POISON GIRLS

[1] “Iyashikei,” TV Tropes, July 10, 2011.

[2] “Beware the Silly Ones,” TV Tropes, accessed June 8, 2017.

[3] “Berserk Button,” TV Tropes, accessed June 8, 2017.

[4] “Abhorrent Admirer,” TV Tropes, accessed June 8, 2017.

[5] Mirai Nikki, 26 episodes, directed by Hosoda Naoto, written by Takayama Katsuhiko, and produced by Asread, aired from October 10, 2011 to April 16, 2012, on Chiba TV and TV Saitama. Based on the Esuno Sakae’s Mirai Nikki, run in Monthly Shōnen Ace (Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten) from July 26, 2006 to December 25, 2010.

[6] Sianne Ngai, Ugly Feelings (Harvard University Press, 2007), 91.

[7] Kier-La Janisse, House of Psychotic Women: An Autobiographical Topography of Female Neurosis in Horror and Exploitation Films (Godalming, Surrey: Fab Press, 2012), 136.

[8] Grafton Tanner, Babbling Corpse: Vaporwave And The Commodification Of Ghosts (Winchester, UK ; Washington, USA: Zero Books, 2016), 16.

[9] Elfen Lied, 13 episodes, directed by Mamoru Kanbe, written by Takao Yoshioka, and produced by Arms, aired on July 25, 2004, on AT-X. Based on Okamoto Lynn’s Elfen Lied, run in Weekly Young Jump (Tokyo: Shueisha) from June 6, 2002, to August 25, 2005.

[10] “Tareme Eyes,” TV Tropes, November 3, 2009.

[11] Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (London; Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012), 64.

[12] Initiated by the videogame Higurashi no Naku Koro ni: Onikakushi-hen, developed and published by 07th Expansion, released August 10, 2002.

[13] Higurashi no Naku Koro ni, 26 episodes, directed by Kon Chiaki, written by Kawase Toshifumi, and produced by Studio Deen, aired from April 4 to September 26, 2006, on Chiba TV, Kansai TV, and Tokai TV.

[14] Christine L. Marran, Poison Woman: Figuring Female Transgression in Modern Japanese Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 163.

[15] Marran, Poison Woman, 128.

[16] Marran, 134–135.

[17] Marran, Poison Woman, 136.

[18] Masahiro Morioka, “A Phenomenological Study of ‘Herbivore Men,’” The Review of Life Studies 4 (September 2013): 1–20.

[19] Lucky Star, 24 episodes, directed by Yutaka Yamamoto and Yasuhiro Takemoto, written by Machida Tōko, and produced by Kyoto Animation, aired from April 8 to September 16, 2007, on Chiba TV, KBS Kyoto, SUN-TV, and Tokyo MX.

[20] Ngai, Ugly Feelings.

[21] Judith E. Fryer Davidov, Felicitous Space: The Imaginative Structures of Edith Wharton and Willa Cather (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1986).

[22] David Ehrlich, “From Kewpies to Minions: A Brief History of Pop Culture Cuteness,” Rolling Stone, July 21, 2015, para. 2.

[23] In Japanese, a “senpai” is a senior at work or an upperclassman at school (“Senpai,” in Wiktionary, accessed June 10, 2017.) The meme “I Hope Senpai Will Notice Me” originated on Tumblr, playing to the cliché scenario of unrequited love common in anime and manga set in high school (“I Hope Senpai Will Notice Me,” Know Your Meme, accessed June 17, 2019.)

[24] Yandere Dev, Don’t Let Senpai Notice You!, 2015.The popularity of moé in twenty-first-century otaku aesthetics has translated into a boom of iyashikei or “healing” anime—slice of life comics and animation with minimal tension, meant to have a calming, even therapeutic impact on audiences.[1] But not all character archetypes blossoming within the moé fandom are about healing. On the contrary, yangire and yandere characters test the limits of cuteness: both are portmanteau words sharing the common prefix yan, from the Japanese verb yamu (病), meaning “to fall ill” or “to be ill,” therefore, the opposite of the healing qualities for which moé is known and celebrated. The gire in yangire comes from kire, meaning “slice,” whereas the dere in yandere comes from deredere, an onomatopoeic word meaning “lovestruck” (dere is a common suffix in moé character types, e.g., tsundere, kūdere, dandere, oujidere, himedere, etc.). The final halves of the words (gire and dere) are what separates the yangire and the yandere in terms of motivation. A compulsion to slice with a knife drives the former; the latter is driven by feelings of love. To cut a long story short (pun intended), the yangire is a cute character prone to snapping into a bloodthirsty psychopath when irritated, frightened or otherwise stressed. In turn, the yandere is a cute character who turns different shades of brutal, obsessive and deranged over their romantic crush. The yandere is a crazy, overprotective stalker in sheep’s clothing, one who will hesitate at nothing (kidnapping, blackmailing, torture, assassination) to remove whatever obstacles stand in the way of their love. Even if that means, in extreme cases, “protecting” their loved one from themselves by maiming or killing them. [Figure 1]

The yangire and yandere fit broadly into the umbrella category of split personality tropes. Beware of the silly, nice, quiet ones, for under the façade of innocence, Mr. Hyde waits seething, ready to burst from their slumber in the form of violent mood swings and sudden outbursts of murderous rage.[2] Often, these are triggered by “berserk buttons,” a stimulus or set of stimuli that activate the violent reaction.[3] It is not unusual for these outbursts to physically transform the characters’ appearance by uncutifying them: eyes widen, irises shrink, an evil slasher smile distorts their adorable features. [Figure 2] The occasional male yangire-dere exist in Japanese media, but unsurprisingly, these characters are almost always female, endorsing a longstanding tradition of uncontrollable emotional excesses by hysterical women. Stephen King’s 1987 novel Misery, later adapted to a film starring Kathy Bates as the psychopathic Annie Wilkes, is perhaps the best-known example. [Figure 3] Unlike the typical yangire-dere character, though, whose appearance is indistinguishable from your everyday cute anime or manga girl, Annie is an “abhorrent admirer,” an othered figure who falls outside conventional beauty standards for being ugly, overweight, and dirty.[4] What Annie and the yangire-dere characters in anime and manga do share is that they are not merely emotionally unstable women but infantilized women, in appearance or behavior or both. For instance, yangire-dere girls are often represented as child-like loli characters, while Annie uses nonsense words like “cockadoodie” and refuses to swear despite the extreme violence of her actions.

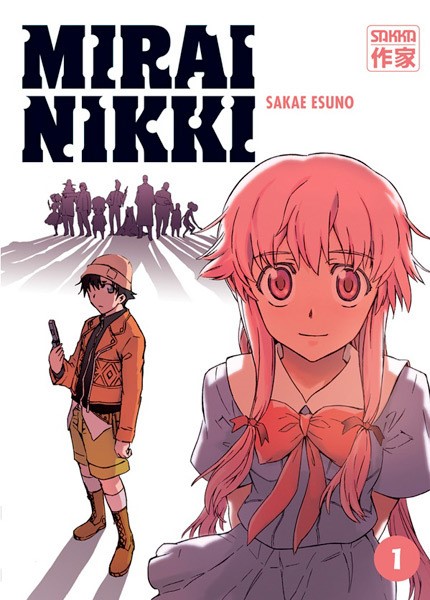

I now turn to some examples of yangire-dere characters in Japanese comics and animation. Gasai Yuno, from the series Mirai Nikki (“Future Diary,” animated in 2011 from Esuno Sakae’s manga),[5] [Figure 4] has become the yandere poster child, originating the Internet meme “Yandere Trance” or “Ecstatic Yandere Pose,” also known as “Yuno face.” Yuno is a cute, pink-haired girl in love with the boy protagonist Amano “Yukkii” Yukiteru, who has been forced to take part in a deadly battle royale. Yuno swears to protect Yukiteru by any means necessary, which in her mind include aggressive stalking and carnage. At the end of the first episode of Mirai Nikki’s anime adaptation (Asread, 2011-12), after a terrified Yukiteru learns of the dreadful fate awaiting him, he is reassured by Yuno, all crazy eyes and blushing, saying “Don’t worry, Yukkii… I will (ahn~) protect you.” [Video 1] The vocal performance by actress Tomosa Murata is not short on erotic undertones.

Along with the dramatic hand pose and eerie lighting, the scene became an exploitable image, with hundreds of fan parodies circulating on the Internet where male and female characters from all kinds of shows are “yanderized” using Yuno’s girlish face as a template. [Figures 5 & 6] The popularity of the Ecstatic Yandere Pose reinforces the idea that, regardless of the character’s biological sex, the affective meanings of the yandere are invariably femininized and infantilized. The yandere thus discloses the paradoxical anxiety we feel towards extreme displays of love and cuteness. Because cuteness is an uncanny deviation from the “standard” human adult appearance, characters who are “too” cute may be perceptualized, at some level, as disturbing, unnatural and deceptive, echoing Mori Masahiro’s uncanny valley—a theory according to which the not-quite-human, as opposed to the nonhuman, evokes especially negative emotions of aversion in viewers.

Another aspect is that, as argued by Sianne Ngai, such marking of subjects as emotionally anomalous, whether by deficit or surplus, is, in fact, a long-running means of othering and disenfranchising those perceived to be outside the various spheres of social privilege (white, male, hetero-cis, abled, and so on). Ngai’s concept of “animatedness” (the state of being moved) effectively pinpoints the ideologically “ambiguous interplay between agitated things and deactivated persons,” “the passionate and the mechanical,”[6] often found in possessed female bodies within the horror genre. In House of Psychotic Women, a semi-autobiographical book on representations of female neurosis in horror and exploitation films, Kier-La Janisse compares her own experience of mental illness with cinema’s most notorious teenage girl possessed by the devil. “I felt like Regan in The Exorcist,” she writes, “emitting these crude and venomous insults while simultaneously feeling that the words were coming from somebody else.”[7] [Figure 7] The yangire-dere are also, among moé’s repertoire of stock characters, those most “possessed” by an emotional defectiveness, haunted by a sense of ventriloquism and manipulation of their voices and bodies as they alternate between innocence and monstrosity. For yangire-dere characters, their state of “animatedness”—that Ngai traces back to rudimentary technologies of animating pictures to which manga, anime, and videogames are tellingly related—reflects the terrifying prospect of being a puppet whose agency is compromised. As Grafton Tanner suggests, “Perhaps for humans, we fear not the mechanization and loss of control so much as the fear of becoming Frankenstein’s monster—a babbling corpse, hollow yet able to run amok with machinelike skill.”[8] Such terror is valid for humans in general, but mainly for those coming from a subaltern viewpoint, who most vividly experience the violence of reification processes.

One notable example of the yangire-dere’s link to puppeteering is the beginning of Elfen Lied (Arms, 2004),[9] an anime adapted from Okamoto Lynn’s homonymous manga. The series focuses on the interactions between humans and a mutant species, the diclonii, whose appearance is similar to people except for two horns on their heads. Elfen Lied’s opening sequence is notorious for its use of graphic violence and “blood piñatas,” i.e., characters whose sole purpose in the story is to be reduced to a pulp. As the main character, the diclonii known as Lucy—who, incidentally, is a cute pink-haired girl, like Mirai Nikki’s Yuno—makes her escape out of an experimentation facility, she uses her invisible telekinetic tentacle‑arms to mutilate and kill her captors, leaving a blood bath in her wake. [Figure 8, Video 2] During this sequence, Lucy becomes both puppeteer and puppet, pulling strings with unseen hands while rendered mechanical and dehumanized by her unstoppable advance. The scene is memorable for the contrast between Lucy’s naked body and the full metal mask engulfing her face, which symbolically inhibits her voice, making her silent during the whole sequence. Lucy’s silence reinforces the automatized quality of the diclonii’s desensitization, who does not babble but runs amok like a vengeful spirit or ghost. Eventually, Lucy is shot in the head, causing her to develop the alternate persona, Nyu, an adorable, innocent, and clumsy feral child, who is taken in by a young man and woman, and named after the only word she produces (“nyu~”). In terms of physical appearance, Nyu is distinguished from Lucy by her zany dojikko (“clumsy” or “ditzy girl”) body language, as well as her tareme, a kind of puppy-dog eyes dropped at the corners, typical of sweet and naïve animanga characters.[10] [Figure 9] This split between Lucy, the person of mass destruction, and Nyu, the ingénue, goes on to become one of the series’ central plot points. But the opening sequence remains especially operative in its representation of the yangire-dere’s ambiguous agency: at once the most aggressively innervated, and the most possessed, of moé’s character types.

If “cuteness is an aestheticization of powerlessness,”[11] the yangire and yandere may be perceived as a revenge of the cutified subject, sadistically lashing out against their master’s sadism. It is no wonder that the yangire-dere’s behavior is so often justified by past trauma, making them sufferers of physical and psychological abuse, in a circular logic where the victim becomes a perpetrator. This vicious circle is present in both Mirai Nikki and Elfen Lied, as Yuno was physically harmed and starved by her parents after failing to live up to their expectations, and the diclonii’s violence is hinted to be the result of abuse by humans. The experience of abjection, of being cast off and reduced to a state of helplessness, pitifulness, and despair, is pivotal in the portrayal and development of many of these characters.

Another example is Ryūgū Rena, an iconic yangire from the best-selling media franchise Higurashi no Naku Koro ni (“When the Cicadas Cry,” 2002–2014).[12] [Figure 10] Scarred by her parents’ divorce, Rena, who is a sweet and friendly girl except when she is not, suffers from acute maternal and self‑abjection. She hallucinates that her mother’s blood is filled with maggots and cuts herself in an attempt to remove it from her body. [Figure 11] Rena is also fascinated with the town’s illegal dumping site, where she passes her time treasure‑hunting for “cute” things, often odd and discarded items that appeal only to herself, suggesting that cuteness, both for Rena and the audience who loves her, is in the eyes of the beholder. [Figure 12] Rena becomes remarkably violent when she is angry and carries around a Japanese gardening hatchet (nata) found in the trash heap, that she uses as her trademark item and weapon. [Figure 13] Although love interests do not define her neurosis, Rena has her yandere moments, such as the famous door sequence in Higurashi no Naku Koro ni’s anime adaptation (Studio Deen, 2006)[13] where she attempts to force her way into the protagonist’s, Maebara Keiichi, house. [Video 3] When Keiichi offers a ragged excuse for refusing to let her in, Rena, who due to her parents’ divorce hates being lied to by the people close to her, screams at him “YOU’RE LYING.” After that, she proceeds to describe in detail Keiichi’s movements that day, suggesting that she had been stalking him all along, and forcefully shakes the door chain. Terrified, Keiichi shuts the door in an attempt to keep her away, brutally crushing Rena’s fingers in the process.

In real life, the genealogy of the yandere can be traced back to the Sada Abe Incident of 1936. Abe was a prostitute and murderess who erotically strangled her lover to death, castrated his corpse, and carried the genitalia in her handbag around the streets of Tokyo for days until her arrest. [Figure 14] When asked why she did it, her reply could hardly be more yandere-ish: “I loved him so much I couldn’t stand it, so I decided that I wanted him all to myself.”[14] Abe’s actions and personality captured Japan’s public imagination and fueled the artistic movement known as ero-guro nonsense. As the police investigation advanced, relevant details about Abe’s life came to light. It was discovered, for instance, that Abe had been a victim of acquaintance rape, which at the time sentenced girls at an early age to the marginality of unmarried women perceived as “damaged goods.” This event precipitated a series of tragic results in her life. Abe became a runaway misfit and, as punishment, was forced into prostitution by her father. Maltreatment by pimps marked her days as a sex worker, contracting syphilis, financial desperation, imprisonment in geisha houses, and eventually becoming a fugitive prostitute. Abe herself acknowledged that her actions were, to some extent, motivated by gender and class disempowerment, resorting to murder and mutilation to gain sexual equality with man.

Still, as scholar Christine Marran points out, the coeval pre-war discourses on Abe were mostly naturalized and cautionary, depoliticizing her claims by framing Abe as an instinctual killer driven by primal bodily desires, repeatedly described as infantile, insect- and animal-like, primitive and regressive.[15] Her tale of psychosexual deviancy became a warning against the dangers of unregulated sexual maturation in females, (ab)used to validate an agenda of gender oppression.[16] As such, Abe came to embody, the dokufu, the “evil” or “poison woman,” an archetype aligning female criminality with the potential for havoc in every woman’s libido. [Figure 15]

In a surprising turn of events, Japanese post-war pulp fiction and 1970s films refashioned Abe as an icon of emancipation. [Figure 16] Although, according to Marran, this shift had less to do with women’s struggle than with the emergence of the “male masochist” as a new counter-discourse of masculinity “through which masculine totalitarian politic and cultural values are explored and critiqued.”[17] Indeed, because male otaku are perceived to be lacking in the traditional predatory qualities of machismo, they are often caught up in debates about “new masculinities” in Japan, associated with phenomena such as the “herbivore men” (sōshoku-kei danshi, young bachelors with no interest in sex and marriage). Arguably, yandere characters like Mirai Nikki’s Yuno also reflect an uneasiness towards the dissolution of “manliness,”[18] cautioning well-intentioned young men that they can become easy prey for the femme fatale feeding off their gentle nature. As the series progresses, we realize that Yuno is not an entirely flat character—that she is fighting her own demons—but Mirai Nikki nevertheless remains a narrative primarily centered on Yukii, thus inheriting the male masochism and grotesque tone of ero-guro works.

Yangire and yandere characters are sensationalistic and shock-based, combining otherwise benign moé characters with the negatively charged transgressiveness of the “poison woman.” Such lurid combination sets series like Mirai Nikki and Elfen Lied apart from more profound, more considerate and complete portraits of insanity and depression in anime and manga (for example, series like Neon Genesis Evangelion). “Poison girls” are bad (identity) politics: they maintain harmful myths about female mental illness, turning psychopathological women into distorted caricatures, more revealing of male fears than anything else. But their broader value might perhaps be found elsewhere—in the realm of abject aesthetics, beyond the good (socially progressive) representation of femininity and female bodies.

Take, for instance, Akira Kogami from Lucky Star (Kyoto Animation, 2007),[19] a quintessential moé anime based on Kagami Yoshimizu’s yonkoma manga (“four-panel comic strip”). [Figure 17] Akira is a 14-year-old idol who, along with her male assistant Minoru, co-hosts “Lucky Channel,” a short infomercial at the end of every episode of Lucky Star, that—supposedly—promotes the main show’s characters. Akira has pink hair (see a pattern?), wears a sailor suit with oversized sleeves, and exhibits an energetic “cute on steroids” persona. However, this is a cover-up for the hardboiled misanthrope lurking underneath the surface. The real Akira is not above resorting to verbal and physical abuse to enforce her will. As episodes go by the joke is that, despite her assistant’s best efforts, Akira’s toxic personality invariably diverts “Lucky Channel” away from its original purpose as a fan corner. Instead, she turns it into a self-contained black comedy of the duo’s increasingly abusive and violent work relationship. Mind you: in typical “poison girl” fashion, the violence is almost entirely female on male.

“Lucky Channel” differs from the actual show not only by breaking the fourth wall but also in tone. Whereas Lucky Star is a “healing” slice of life show, “Lucky Channel” is dark, innervated, cynical. Additionally, Akira’s “yangireness” is openly framed as a labor issue, presenting her neurosis as the result of early enrolment at age three into the highly competitive tarento (“television celebrity”) industry. Among other gritty details, we learn that her parents are divorced and that her mother takes charge over Akira’s money, allegedly using it to buy herself branded goods while giving her daughter a puny allowance. Akira is represented as a slave to the wage, bitter over the pressure and expectations of an exploitative industry, family, and public alike, yet obsessed with career advancement, power, and prestige. Like a reverse-Regan, her body is possessed by a labor-intensive cute persona, which easily crumbles into unladylike and unchildlike poses and gestures like crotch-scratching and chain-smoking, squinty eyes, and a harsh voice. [Video 4]

Moreover, because Akira perceives her being relegated to the other side of the “wall” as a status inequality, she becomes petty and paranoid, resenting the protagonists for their popularity. She longs to be in the main show and envy overcomes her, an emotion that, as Ngai points out, is historically feminized and proletarianized—with the infamous concept of “penis envy” in the eye of the storm.[20] As a result, Akira bullies her subordinate, Minoru, who plays a minor role in the main show and whose mobility irritates her the most, in remarkably cruel ways ranging from verbal humiliation to escalating forms of physical violence, including an ashtray thrown at his face. [Figure 5a, b] Akira’s own repeated attempts at entering the main show are always frustrated. At various occasions, she abruptly falls ill on the day of her debut, is given a karaoke room instead of a concert hall, and stopped short in her song. The message is clear: Akira is not allowed into Lucky Star’s fictional world, inhabited by students and workers unaffected by work’s toll on the body and soul of the workforce. In the end, Akira’s poisonousness brings upon the destruction of the “Lucky Channel” itself. After being sent on a life-threatening mission to collect drinking water from the springs of Mount Fuji, which Akira ends up spitting for not being sufficiently cool, Minoru is pushed beyond his breaking point and goes on a rampage that destroys the “Lucky Channel” set. [Video 6]

The yangire-dere potentially embody this destructive cycle of abuse in a transgressive but not progressive way, aiming for outright negativity rather than realism or proper representation. They express our fear of the repressed, whether the psychological or social-economical repressed, resembling Jung’s principle of enantiodromia, that extremes transmogrify into their shadow opposites. The cuter and more domesticated the girl, then, the darker and wilder her poison, explaining why many yangire and yandere characters have pink hair or other explicit markers of cuteness and conventional feminity. Furthermore, these “poison girls” draw our attention to the invisible threads weaving together issues of gender, intimacy, agency, and violence in media and commodities. They suggest that the reverse of the Shakespearean saying that there is a method to the madness is just as accurate: that there is a madness to the method. In doubt, take a stroll down your nearest Ikea or Muji store, where the sheer superabundance of order and utilitarianism is enough to drive anyone crazy. [Figure 18] Indeed, the exhaustive partitioning of the private and domestic spaces traditionally assigned to femininity demonstrates that, as Judith Fryer argues, “The structures that contain—or fail to contain—women are the houses in which they live, the material things of their lives.”[21]

The value of yangire and yandere characters is, precisely, that their madness is a result of the systemic violence unfolding from the commodification of female and infantile bodies, in this case, in the form of a “cuteness‑industrial complex.”[22] Characters like Yuno, Lucy, Rena, and Akira are scary because, despite their cuteness, they are intelligent and resourceful; they stalk, attack, and murder methodically. An excellent example of this trope in Western media is Gone Girl, a 2012 novel by Gillian Flynn, adapted to a film directed by David Fincher in 2014. In it, the female protagonist Amy Elliott Dunne is also “infantilized” by her serving as inspiration for the popular Amazing Amy children’s book series, written by Amy’s exploitative parents, and traumatized by their emotionally absent relationship to her. When Amy’s marriage disintegrates, she carries out an extraordinarily intricate and carefully executed plan to frame husband Nick for her own murder, to get back at his neglect and adultery. The plan includes, among other things, a meticulously fabricated diary detailing Amy’s isolation and fear, taking a urine sample from a pregnant neighbor to fake a pregnancy test, draining her blood to plant evidence of violent injuries around the house, [Figure 19] and raising her life insurance so it seems like Nick killed her for the money. Such dangling on the thin line separating reason from the insanity, the lovable from the horrific, is also valid for many over-sentimental dialogues and displays of romantic love in women-oriented products like shōjo manga that, if taken out of context, could easily pass for yandere scenarios of a dangerous obsession. [Figure 20]

The procedural aspect of the yangire and yandere’s madness is the subject of a popular videogame, the Yandere Simulator (yanderesimulator.com), presently in development by American fan creator YandereDev since 2014. [Figure 21] With the subtitle “Don’t Let Senpai Notice You,” a pun on the Internet meme “I Hope Senpai Will Notice Me,”[23] YandereDev describes the Yandere Simulator as “a stealth game about stalking a boy and secretly eliminating any girl who seems interested in him, while maintaining the image of an innocent schoolgirl.” The player controls a Japanese high school student named Aishi “Yan-chan” Ayano, who must eliminate her love rivals one by one. To do this, she uses an extensive collection of methods, from slaughter to staging accidents to social sabotage, while dealing with practical concerns such as disposing of corpses, cleaning up blood or destroying evidence. In a promotional video, the narrator stresses that the “Yandere Simulator is not a dating sim. It’s not about romancing senpai, it’s about being a stalker. And it’s about sabotaging his love life from the shadows.”[24] [Figure 22] If Yan‑chan becomes noticeable by insisting on pursuing her love interest face to face, or if he catches Yan‑chan acting suspicious, she will be met with accusations of being “weird,” “creepy” or “crazy,” and her senpai will scream at her to stay away. “Senpai is a nice person,” the narrator says, “however, everyone has their limits.” The fact that Yan-chan’s love interest must not notice her contradicts every rule of typical romance narrative. Like Lucky Channel’s Akira, it is as if Yan‑chan is too corrupt for the world of romance and dating sims in which she wants in. Unsurprisingly, the Yandere Simulator is rendered in cute animanga visuals, with the game logo and the intro screen painted in bright pink with hearts serving as decorative elements. What is more, the Yandere Simulator development blog, in which YandereDev details the process of feature building, debugging, and fan feedback involved in constructing the game, is in and of itself a window into the exhaustive method involved in building the yandere’s madness.

The seemingly infinite elasticity of what can be considered “cute” in Japanese popular culture has originated characters in which “psycho” traits substitute moé’s healing qualities. But the sensationalism of yangire and yandere tropes does not stop them from becoming remarkably opaque at times, appealing to both radical and reactionary readings. Between the extreme oppositions of cuteness and horror, reason and madness, submission and domination, is a gap in which reverberate visions of female and male trauma. Indeed, while most yangire-dere characters come off as bad representations of feminized and infantilized subjects, there is often an experience of disenfranchisement at the root, indexing both a fear and a desire that subaltern subjects will rebel against the oppressive forces that shape their affective-aesthetic milieu. As such, the “poison girls” in manga, anime, and videogames also stage a broader tension perceived to exist between the regulation and commodification of the spheres traditionally assigned to women and children, the home and family, and their shadow opposite: out of control violence. Above all, yangire and yandere characters express the everlasting conflict between Eros and Thanatos, the drives towards life-love and death, in a concentrated way that probes into our deep-seated feelings of suspicion towards anything that is exceedingly nice.

See in CUTENCYCLOPEDIA – Absolute Boyfriend & She’s Not Your Waifu, She’s an Eldritch Abomination.

See in PORTFOLIO – Attack of the Bloodsucking, Man-Eating Ghouls, Muji Life + Yandere/Yangire & They Say That Clovers Blossom From Promises.

REFERENCES in Poison Girls.

Mild spoilers

Mirai Nikki ("Future Diary" anime, manga)Elfen Lied (anime, manga)Higurashi no Naku Koro ni ("Higurashi: When They Cry" anime)Lucky Star (anime)

major spoilers

Gone Girl (film)

CONTENT NOTICE

This entry is potentially disturbing or unsuited for some readers.Mentions or depictions of abuse, blood, death,

excessive or gratuitous violence, guns/weapons, mental illness, misogyny, self-harm, and sexual assault.Figure 1 The character Gasai Yuno, from Mirai Nikki (“Future Diary”), is the yandere poster child. Source: Mirai Nikki, 26 episodes, directed by Hosoda Naoto, written by Takayama Katsuhiko, and produced by Asread, aired from October 10, 2011, to April 16, 2012, on Chiba TV and TV Saitama. Based on the manga series by Esuno Sakae.

Figure 2 Typical yandere eyes and facial expressions. Source.

Figure 3 Misery’s Annie Wilkes (Kathy Bates) with her hammer. Source: Misery, directed by Rob Reiner, Los Angeles (CA): Columbia Pictures. Based on the novel by Stephen King, 1990.

Figure 4 Cover of the first volume of Esuno Sakae’s Mirai Nikki, published by Kadokawa Shoten on July 26, 2006, with Yuno in the foreground and Yukii standing behind her. Source.

Video 1 Yandere Trance or Ecstatic Yandere Pose sequence from the Mirai Nikki anime. Source: Mirai Nikki, episode 1, “Sign Up,” directed by Hosoda Naoto, written by Takayama Katsuhiko, and produced by Asread, aired from October 10, 2011, to April 16, 2012, on Chiba TV and TV Saitama. Based on the manga series by Esuno Sakae (via).

Figure 5 Figure 5 (left) How to “yanderize” characters, using the popular Kirino Kousaka from Oreimo as example. Source.

Figure 6 Fan art representing the character from popular anime series (Touhou Project, Nichijou, Naruto, Yu-Gi-Oh!) in Yuno’s yandere pose. Source.

Figure 7 The body of 12 year-old Regan, posed by the Devil in The Exorcist. Source: The Exorcist, directed by William Friedkin, Burbank (CA): Warner Bros, 1973. Based on the novel by William Peter Blatty (GIF via).

Figure 8 The diclonii Lucy in Elfen Lied. The right side of her face shows the helmet used during the anime’s opening sequence. Source.

Video 2 Some of the first, very bloody moments of Elfen Lied. Source: Elfen Lied, episode 1, “BEGEGNUNG,” directed by Mamoru Kanbe, written by Takao Yoshioka, and produced by Arms, aired on July 25, 2004, on AT-X. Based on the manga series by Okamoto Lynn (via).

Figure 9 Physically, Nyu is distinguished from Lucy by her tarime, i.e., sweet droopy eyes. Source: Elfen Lied, 13 episodes, directed by Kanbe Mamoru, written by Yoshioka Takao, and produced by Arms, aired from July 25 to October 17, 2004, on AT-X. Based on the manga series by Okamoto Lynn (GIF via).

Figure 10 Ryūgū Rena character sprite from the first dōjin (self-published) visual novel of the Higurashi franchise. Source: Higurashi no Naku Koro ni: Onikakushi-hen, developed and published by 07th Expansion, released August 10, 2002.

Figure 11 Rena hallucinating about the maggots in her blood. Source: Higurashi no Naku Koro ni, 26 episodes, directed by Kon Chiaki, written by Kawase Toshifumi, and produced by Studio Deen, aired from April 4 to September 26, 2006, on Chiba TV, Kansai TV, and Tokai TV (GIF via).

Figure 12 The dump in Higurashi no Naku no Koro ni. Rena has a “secret base” (a van emptied and filled with things that she likes), to which she retreats when she is feeling anguished. Source: Higurashi no Naku Koro ni.

Figure 13 Rena holding her hatchet or nata (a Japanese gardening tool). Source: Higurashi no Naku Koro ni.

Video 3 The yandere sequence between Rena and her love interest in the Higurashi no Naku Koro ni anime. Higurashi no Naku Koro ni, episode 4, “Onikakushi-hen Sono Yon – Yugami,” directed by Kon Chiaki, written by Kawase Toshifumi, and produced by Studio Dee, aired from April 25, 2006, on Chiba TV, Kansai TV, and Tokai TV (via).

Figure 14 Sada Abe shortly after her arrest in 1936, at the Takanawa police station in Tokyo. Source.

Figure 15 The “dokufu” (“poison-woman”) became a buzzword during the Meiji Era, translating the public fear of an epidemic of deviant, murderous women. Oden Takahashi, represented in the figure, is considered the most iconic dokufu of the time. Source.

Figure 16 Still from the 1975 soft core “pink film” A Woman Called Abe Sada (1975), by Tanaka Noboru.

Figure 17 Still from the 1975 softcore “pink film” A Woman Called Abe Sada (1975), by Tanaka Noboru. Source.

Video 4 Akira’s double personality in “Lucky Channel.” Source: Lucky Star, 24 episodes, directed by Yutaka Yamamoto and Yasuhiro Takemoto, written by Machida Tōko, and produced by Kyoto Animation, aired from April 8 to September 16, 2007, on Chiba TV, KBS Kyoto, SUN-TV, and Tokyo MX (via).

Video 5a Examples of Akira’s verbal abuse and bullying over Minoru. Source: Lucky Star (via).

Video 5b Akira bullying Minoru. Source: Lucky Star (via).

Video 6 Minoru finally going berserk after dues to Akira’s abuse, leaves the set of “Lucky Channel” in ruins. Source: Lucky Star (via).

Figure 18 A promotional image of Muji’s home storage and organization. Source.

Figure 19 Gone Girl’s Amy Dunne planting traces of wiped blood on the kitchen floor. Source: Gone Girl, directed by David Fincher, Los Angeles (CA): 20th Century Fox, 2014. Based on the novel by Gillian Flynn (GIF via).

Figure 20 An example of romantic speech in a shōjo manga with a yandere tone (panel from Last Game, by Amano Shinobu). Source.

Figure 21 Promotional illustration by Jowa of the videogame Yandere Simulator, showing a smitten high school with a track of blood and corpses in her wake. Source.

Video 7 Short presentation and tutorial of Yandere Simulator. Source.

ABSOLUTE BOYFRIEND ; (BETAMALE) ; BLINGEE ; CGDCT ; CREEPYPASTA ; DARK WEB BAKE SALE ; END, THE ; FAIRIES ; FLOATING DAKIMAKURA ; GAIJIN MANGAKA ; GAKKOGURASHI ; GESAMPTCUTEWERK; GRIMES, NOKIA, YOLANDI ; HAMSTER ; HIRO UNIVERSE ; IKA-TAKO VIRUS ; IT GIRL ; METAMORPHOSIS ; NOTHING THAT’S REALLY THERE; PARADOG ; PASTEL TURN ; POISON GIRLS ; POPPY ; RED TOAD TUMBLR POST ; SHE’S NOT YOUR WAIFU, SHE’S AN ELDRITCH ABOMINATION ; ZOMBIEFLAT