LOOT BOX

28 jan – 28 FEB, 2020 @ Biblioteca FCT/UNL (almada, PT)

THREE-PERSON SHOW W/ ANDRÉ PEREIRA & MAO +

About

Loot Box is an exhibition of the artist collective MASSACRE, formed by André Pereira, Hetamoé and Mao, which transposes the idea of graphic narrative to media such as drawing, video, and installation, in works specially conceived for the library of the Faculty of Science and Technology of the NOVA University, in Almada, Portugal.

In the videogame industry, the term “loot box” is used to refer to a random selection system—akin to a sachet of collectible cards—for obtaining virtual items or performance bonuses. These are “treasure" that you discover or are rewarded with upon completion of a goal, in a logic that goes back to roleplaying games like Dungeons & Dragons, promoting the looting of enemies and desecration of corpses. Despite its recontextualization in today's online games, the causality “to the victor go the spoils" remains in the etymology of the term. Recently, loot boxes have been the subject of scrutiny for the way they monetize certain aspects of the game, creating pay to win schemes in which players depend on a real financial investment to progress virtually.

This exhibition treats the “loot box" as an extended model which, in addition to its explicit and functional content, contains ways of thinking inherent to the extractivistic ideologies responsible for the environmental breakdown in the Anthropocene. “Gamified," the economy discovers a new market that seems to fulfill a fantasy of endless growth.

/Loot Box é uma exposição do colectivo artístico MASSACRE, composto por André Pereira, Hetamoé e Mao, que transpõe a ideia de narrativa gráfica para meios como o desenho, vídeo e a instalação, em trabalhos concebidos especialmente para a Biblioteca FCT/UNL.

Na indústria dos videojogos, o termo loot box (“caixa de saque”) denomina sistemas de sorteio—aleatório, como uma saqueta de cromos—para obtenção de itens ou bónus de desempenho virtuais. São “tesouro” que se descobre ou com o qual se é recompensado após a conclusão de um objectivo, numa lógica que remonta aos roleplaying games como Dungeons & Dragons, promovendo o saque dos inimigos e profanação de cadáveres. Apesar da sua recontextualização nos jogos online actuais, a causalidade “ao vencedor, os despojos” mantém-se na etimologia do termo. Recentemente, as loot boxes têm sido alvo de escrutínio pela forma como monetizam certos aspectos do jogo, criando sistemas de pay to win em que os jogadores dependem de um investimento financeiro real para progredir virtualmente.

Esta exposição trata a loot box enquanto modelo alargado que, além do seu conteúdo explícito e funcional, encerra formas de pensar inerentes às ideologias extractivistas responsáveis pela ruptura ambiental no Antropocénico. “Gamificada", a economia descobre um novo mercado que parece cumprir uma fantasia de crescimento interminável.

HETAMOÉ

En plein air (after Zelda), 2020.

Archival ink markers on Bristol paper mounted on foamcore, model trees, grass mats, trolleys and toy signs, laser prints on fluorescent cardboard, on black foamcore bases. Variable dimensions.Marcadores de tinta de arquivo sobre cartolinas Bristol montadas em papéis-pluma, árvores-modelo, tapetes de relva, carrinhos e sinalética de brincar, impressões a laser sobre cartolinas fluorescentes, sobre bases de papel-pluma preto. Dimensões variáveis.En plein air (after Zelda) used the maps from the classic RPG (role-playing game) The Legend of Zelda (Nintendo, 1986) as the starting point for a modular floor installation of marker drawings, the format of which varied weekly during the Loot Box exhibition and which is incremental, i.e., to which pieces keep being added. In this way, it thematized the assetization of nature, translating into a flattening of the great outdoors, reduced to infinitely replicable, interchangeable, and cumulative sprites—a tree, water or ore is a resource ready to be harvested by the player and converted into usable items for completing quests and in-game goals (fuel, beverage, currency, etc.) in diagrammatic and often randomized worlds (e.g., new maps are created every time a game is started). The models, toys and captions also incorporated into the installation reinforce the evocation, present in environmental representations in RPGs and strategy videogames, of notions of commodification, such as monoculture, clear cutting, extractivism, and so on. The captions included phrases from the epoch-making text adventure Zork I—for instance, “You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door”—featuring descriptions of natural and fantastic landscapes (forests, lakes, dungeons, mazes), criteria for player evaluation (“when you find a valuable object and pick it up, you receive a certain number of points”) and treasure items (gemstones, rare ores, coin bags or chests, etc.).

The work took advantage of the particular architecture of the FCT library so that it could be fully observed by the audience positioned in the staircases and upper floors, playing with the tension between horizontality and verticality in these territorial depictions: from the computer screen where such fantastic adventures unfold before the eyes of the gamers, to the plane of the floor traditionally associated with cartography. Additionally, En plein air (after Zelda) puts video games in conversation with the broader history of landscape painting. The act of painting in the open air (en plein air) by the naturalist school of Barbizon and the impressionists in the 19th century was a decisive moment for modernism in the West, in which painting was projected to the outdoors, beyond the confines of the academies. About a century later, the expansive worlds in videogames like The Legend of Zelda, created in Japan by game designers Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka, retreated into players' rooms and personal computers. As such, an ironic, even perverse relationship is established with modernist narratives of autonomy and medium specificity—the flatness of pixel art, meticulously rendered in colorful markers, may evoke the Japanese prints that so influenced modern painters, or the formalisms from geometric abstraction to hard-edge and color-field painting; but these are irredeemably transfigured by the playfulness and cuteness of early videogames, whose stylistic over-simplification is closer to that of pop characters like Hello Kitty.

/En plein air (after Zelda) tomou os mapas do RPG clássico The Legend of Zelda (Nintendo, 1986) como ponto de partida para uma instalação modular de chão, composta por desenhos a marcador, cujo formato variou semanalmente durante a exposição Loot Box e que é incremental, ou seja, à qual vão sendo acrescentadas peças. Tematizou-se, deste modo, a “assetização” (assetization) da natureza, traduzindo-se numa planificação do ar livre, reduzido a sprites infinitamente replicáveis, permutáveis e acumuláveis: cada árvore, água ou minério é um recurso pronto a ser colhido pelo jogador e convertido em itens utilizáveis para o cumprimento de aventuras e missões dentro do jogo (combustível, bebida, moeda, etc.) em mundos diagramáticos e, frequentemente, aleatorizados (em que novos mapas são criados de cada vez que se começa um jogo). Os artigos de modelismo, brinquedos e legendas também incorporados na instalação reforçam a evocação, muitas vezes presente nas representações do meio natural em RPGs e videojogos de estratégia, de noções de comercialização como a monocultura, o clear cutting ou o extractivismo, entre outras. As legendas incluem frases da text adventure fundacional Zork I—por exemplo, “You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door”—com descrições de paisagens naturais e fantásticas (florestas, lagos, masmorras, labirintos), critérios de avaliação dos jogadores (“when you find a valuable object and pick it up, you receive a certain number of points”) e itens de tesouro (pedras preciosas, metais raros, sacos e arcas de moedas, etc.).

A obra tirou partido da arquitectura específica da biblioteca da FCT para que fosse observável na totalidade pelo público posicionado nas escadarias e pisos superiores, jogando com a tensão entre a horizontalidade e a verticalidade nestas representações do território: do ecrã do computador onde se desenrolam as aventuras fantásticas perante os olhos dos gamers, ao plano do chão tradicionalmente associado à cartografia. Adicionalmente, En plein air (after Zelda) coloca os videojogos em diálogo com a história da pintura de paisagem. O acto de pintar ao ar livre (en plein air) pela escola naturalista de Barbizon e pelos impressionistas no século XIX foi um momento decisivo para o modernismo no Ocidente em que a pintura se projectou para os exteriores, fora dos confins das academias. Cerca de um século depois, os mundos expansivos de videojogos como The Legend of Zelda, criado no Japão pelos game designers Shigeru Miyamoto e Takashi Tezuka, recolheram-se para dentro dos quartos e computadores pessoais dos jogadores. Assim, estabelece-se uma relação irónica, talvez perversa, com as narrativas modernistas de autonomia e especificidade do meio—a planura da pixel art, meticulosamente reproduzida com marcadores coloridos, poderá evocar as estampas japonesas que tanto influenciaram os pintores modernos, ou mesmo os formalismos da abstracção geométrica à pintura hard-edge e color-field; mas estes, irremediavelmente, transfigurados pela ludicidade e cuteness dos primeiros videojogos, cuja sobre-simplificação estilística está mais próxima de personagens pop como a Hello Kitty.

HETAMOÉ

Digitália, 2020.

Giclée prints, archival ink markers on Bristol paper with frames. Variable dimensions. Impressões glicée, marcadores de tinta de arquivo sobre cartolinas Bristol com molduras. Dimensões variáveis.This collection of drawings and prints based on various sources—for example, Internet GIFs, videogame avatars, intrusive browser ads, Japanese animation, 3D models or phone photography—addresses the intersection between the digital image’s glossy appeal and the polluted and pollutive aesthetics to which it is often associated. From the cultural “pollution” arising from videogames and cyberculture’s lowbrow reputation to the material degradation of the images themselves (glitches, blurring, pixilation, etc.), there hangs the threat of a deviant substrate under the attractive façade.

The photographs present in the collection are details of landscapes from the FCT campus, capturing the ambivalence between natural elements and "artifacts" in the digital sense: that is, unwanted aspects in the images, whether these are physical debris or graphic imperfections resulting from a phone camera.

/Nesta colecção de desenhos e impressões baseados em fontes diversas—por exemplo, GIFs da Internet, avatares de videojogos, publicidade intrusiva de browsers, animação japonesa, modelos 3D ou fotografias de telemóvel—trabalha-se a intersecção entre o apelo lustroso das imagens digitais e uma estética poluída e poluidora, a que muitas vezes estas surgem associadas. Desde a “poluição” cultural que resulta da reputação lowbrow dos videojogos e cibercultura até à degradação material das imagens em si (glitches, desfocamentos, pixelização, etc.), paira a ameaça de um substracto desviante sob a fachada atraente.

As fotografias presentes na montagem são detalhes de paisagens do campus da FCT, captando a ambivalência entre os elementos naturais e “artefactos” no sentido digital: ou seja, aspectos indesejados nas imagens, sejam estes o lixo físico ou imperfeições gráficas resultantes de uma câmara de telemóvel.

HETAMOÉ

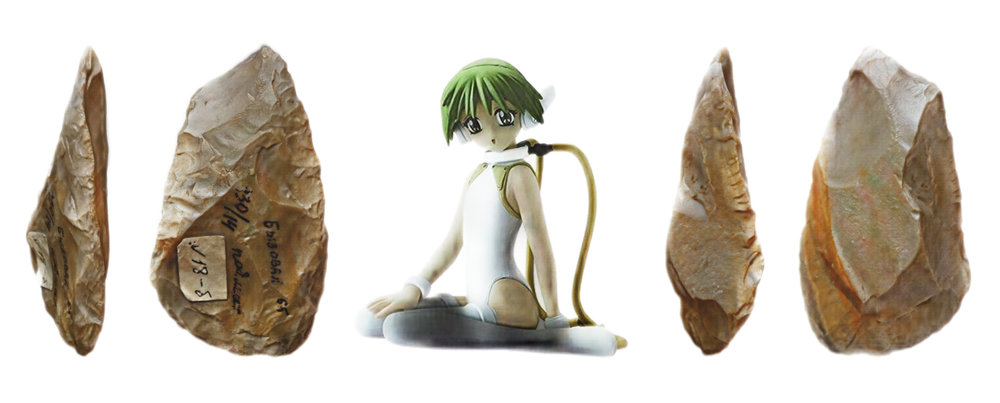

Lootbox_compilation.mp4, 2020.

Digital video, 2’45’’Vídeo digital, 2’45’’This short video compiles a sequence of loot box GIFs from various videogames, including a couple of reactions by players to receiving their prizes. The GIFs were, in turn, subjected to moshing effects, generating distortions that compromise the original function of the loot boxes. The soundtrack results from the distension of the blinging sounds that often accompany the opening of these virtual items.

The video is accompanied by pieces of debris collected in the FCT campus, to which subtitles with items of "treasure" (loot) are superimposed, fictionalizing the excrement of human construction activities through a fantasy plane.

/Neste pequeno vídeo, compilam-se uma sequência de GIFs de loot boxes de videojogos diversos, incluindo algumas reacções por parte dos jogadores ao receberem os seus prémios. Os GIFs foram, por sua vez, sujeitos a efeitos de moshing, gerando distorções que comprometem a função original das “caixas de saque”. A banda sonora resulta da distensão dos sons tintinantes que muitas vezes acompanham a abertura destes itens virtuais.

O vídeo é acompanhado por peças de entulho recolhidas no campus da FCT, à qual se sobrepõem legendas com itens de “tesouro” (loot), ficcionando-se os excrementos resultantes das actividades de construção humana através de um plano de fantasia.