INTRODUCTION

CUTENESS AND MANGA

[177] Ryan Holmberg, “Matsumoto Katsuji and the American Roots of Kawaii,” The Comics Journal (blog), April 7, 2014, para. 3, http://www.tcj.com/matsumoto-katsuji-and-the-american-roots-of-kawaii/.

[178] “Katsuji Matsumoto,” The Manga (blog), January 15, 2015, http://ngembed-manga.blogspot.com/2015/01/katsuji-matsumoto_15.html.

[179] Cross, The Cute and the Cool, 43–81.

[180] Holmberg, ‘Matsumoto Katsuji and the American Roots of Kawaii’, paras. 7, 15.

[181] Ryan Holmberg, ‘Matsumoto Katsuji: Modern Tomboys and Early Shojo Manga’, in Women’s Manga in Asia and Beyond: Uniting Different Cultures and Identities, ed. Fusami Ogi et al. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 200.

[182] “Katsuji Matsumoto,” in Wikipedia, August 14, 2018, “Kurukuru Kurumi-chan,” https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Katsuji_Matsumoto&oldid=854885031.

[183] Marco Pellitteri, The Dragon and the Dazzle: Models, Strategies, and Identities of Japanese Imagination: A European Perspective (John Libbey Publishing, 2011), 79.

[184] Barbara Hartley, “Performing the Nation: Magazine Images of Women and Girls in the Illustrations of Takabatake Kashō, 1925–1937,” Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific, no. 16 (March 2008), http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue16/hartley.htm.

[185] Holmberg, “Matsumoto Katsuji and the American Roots of Kawaii”; Hartley, “Performing the Nation: Magazine Images of Women and Girls in the Illustrations of Takabatake Kashō, 1925–1937.”

[186] Eico Hanamura, Eico Hanamura, interview by Manami Okazaki and Geoff Johnson, Kawaii!! Japan’s Culture of Cute [book], 2013, 26, https://www.amazon.com/Kawaii-Japans-Culture-Manami-Okazaki/dp/3791347276.

[187] Nozomi Masuda, ‘Shojo Manga and Its Acceptance: What Is the Power of Shojo Manga’, in International Perspectives on Shojo and Shojo Manga: The Influence of Girl Culture, ed. Masami Toku (New York ; London: Routledge, 2015), 24.

[188] Hanamura, Eico Hanamura, 21.

[189] Deborah M. Shamoon, Passionate Friendship: The Aesthetics of Girl’s Culture in Japan (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2012).

[190] Macoto Takahashi, Macoto Takahashi, interview by Manami Okazaki and Geoff Johnson, Kawaii!! Japan’s Culture of Cute [book], 2013, 28, https://www.amazon.com/Kawaii-Japans-Culture-Manami-Okazaki/dp/3791347276.

[191] Rachel ‘Matt’ Thorn, ‘Before the Forty-Niners’, rachel-matt-thorn-en, 12 June 2017, para. 7, https://www.en.matt-thorn.com/single-post/2017/06/12/Before-the-Forty-Niners.

[192] Takahashi, Macoto Takahashi, 28.

[193] “TAKAHASHI Makoto,” Baka-Updates Manga, accessed October 14, 2017, https://www.mangaupdates.com/authors.html?id=7263.

[194] Shiokawa, “Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics,” 101.

[195] Shiokawa, 101.

[196] Natsu Onoda Power, God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga (Jackson Miss.: University Press of Mississippi, 2009); Helen McCarthy and Katsuhiro Otomo, The Art of Osamu Tezuka: God of Manga (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2009).

[197] Pellitteri, The Dragon and the Dazzle, 80, 184.

[198] Pellitteri, 80.

[199] Pellitteri, 80.

[200] Shiokawa, “Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics,” 107.

[201] Other notable authors and works of associated with the Year 24 Group include Ōshima Yumiko’s Banana Bread no Pudding (1978), Wata no Kuni Hoshi (The Star of Cottonland, 1978-87), Yamagishi Ryoko’s Shiroi Heya no Futari (“Couple of the White Room,”1971), Kihara Toshie’s Angelique (1977), Ichijō Yukari’s Maya no Souretsu (“Maya’s Funeral Procession,” 1972), or Morita Jun’s short stories.

[202] Rachel “Matt” Thorn, “Introduction,” in The Heart of Thomas (Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books, 2013), 521.

[203] James Welker, ‘A Brief History of Shonen’ai, Yaoi, and Boys Love’, in Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan, ed. Mark McLelland et al. (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2016), 42–75.

[204] M. J. Johnson, “A Brief History of Yaoi,” Sequential Tart, accessed October 15, 2017, http://www.sequentialtart.com/archive/may02/ao_0502_4.shtml.

[205] J. Keith Vincent, “Making It Real: Ficiton, Desire, and the Queerness of the Beautiful Fighting Girl,” in Beautiful Fighting Girl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

[206] Shiokawa, “Cute but Deadly: Women and Violence in Japanese Comics,” 110.

[207] Shiokawa, 107–12.

[208] Vincent, “Making It Real: Ficiton, Desire, and the Queerness of the Beautiful Fighting Girl,” x.

[209] Setsu Shigematsu, ‘Dimensions of Desire: Sex, Fantasy, and Fetish in Japanese Comics’, in Themes and Issues in Asian Cartooning: Cute, Cheap, Mad, and Sexy, ed. John A. Lent (Bowling Green, OH: Popular Press 1, 1999), 130.

[210] Patrick W. Galbraith, “Lolicon: The Reality of ‘Virtual Child Pornography’ in Japan,” Image and Narrative : Online Magazine of the Visual Narrative 12, no. 1 (March 1, 2011): 102.

[211] Patrick W. Galbraith, The Otaku Encyclopedia: An Insider’s Guide to the Subculture of Cool Japan (Kodansha USA, 2009), 128.

[212] “Dimensions of Desire: Sex, Fantasy, and Fetish in Japanese Comics,” 130.

[213] Galbraith, “Lolicon,” 102.

[214] Comic Market Committee, “What Is the Comic Market?” (COMIKET, 2014), “The 3rd Harumi Era,” https://www.comiket.co.jp/info-a/WhatIsEng201401.pdf.

[215] Murakami, Little Boy, 55.

Figure 49 Excerpt from Mizuno Junko’s grotesque shōjo manga Pure Trance, initially released Booklets with CDs released by Avex Trax from 1996 to 1998, published in English by the Last Gasp in 2015. Source.

Cuteness in Japanese comics and animation has evolved across different demographics and in close relation—sometimes, opposition—to orbiting concepts such as kirei (“pretty”), utsukushii (“beautiful”), jojō (“lyricism”), tanbi (“aesthetics”), or even “undesirable” traits like creepy, ugly, and grotesque, among others. The kawaii permeates both lyrical girls’ comics and action-packed boys’ comics, it seeps into the realm of erotic and pornographic manga, like boys’ love and lolicon, and blends seamlessly with the imagery of horror and psychedelia. Beloved creepy-cute characters from the 1960s, like Mizuki Shigeru’s Kitarō or Umezu Kazuo’s Cat Eyed Boy, Hino Hideshi’s Hell Baby (Gaki Jigoku, 1984), or girls’ manga like Mizuno Junko’s Pure Trance (1996-98), [Figure 49] attest to the vitality of such encounters. In this section, I present an overview of the pivotal role of Japanese comics and animation in the creation, development, and dissemination of kawaii cultures and aesthetics, from its origins in the Interwar period throughout the 2000s.

Figure 50 Panel from Tagawa Suihō’s popular children’s manga Norakuro. Source.

Figure 51 Page from Kasei Tanken by Oguma Hideo (story) and Ooshiro, Noboru (art), depicting a tomato society on Mars. Source.

While kawaii culture boomed in the 1970s, its emergence can be traced back much earlier, to the beginning of the twentieth century and the worldwide rise of children’s consumer culture and entertainment. Norakuro (1931–81), Bōken Dankichi (1933–39), or Tank Tankurō (1934), were popular comic strips or episodic manga featuring human and non-human characters (a dog, a boy, and a robot, respectively) published in boys’ magazines like Shōnen Club during the interwar era. [Figure 50] Much like funny animals in Western children’s books (e.g., The Wind in the Willows), newspaper comic strips (e.g., Krazy Kat), and animated cartoons (e.g., Silly Symphony, Talkartoons, Looney Tunes, or Merrie Melodies), these relied on humor and cute aesthetics to entertain modern adults and children alike. In Japan, later works such as Kasei Tanken (“Expedition to Mars,” 1940), employed cuteness in longer, more sophisticated narratives, reminiscent of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo, [Figure 51] but for the most part, manga remained targeted at children until the 1950s. Matsumoto Katsuji, a late addition to the manga history canon whose work has been rediscovered in two important exhibitions at the Yayoi Museum in Tokyo, in 2006 and 2014,[177] was one of the essential kawaii pioneers. He published comics and illustrations in girls’ magazines—including the ground-breaking shōjo manga Nazo no Clover (“Mysterious Clover,” 1934) [Figure 52a, b]—until he retired in 1955 to illustrate children's fiction, and founded a company specializing in baby goods, that created the widely popular kawaii characters Haamu and Monii.[178] [Figure 53]

Figure 52a Cover of Matsumoto Katsuji’s Nazo no Clover (“Mysterious Clover”), published as a supplement in the girls’ magazine Shōjo no Tomo. Source.

Figure 52b Page from Nazo no Clover. Source.

Figure 53 Matsumoto Katsuji’s characters Haamu and Monii from the 1950s. Source.

Matsumoto’s most popular manga, Kurukuru Kurumi-chan, serialized in the girl’s magazine Shōjo no Tomo (“Girl’s Friend”) from 1938 to 1940, followed the domestic exploits of a spunky little girl called Kurumi (“walnut”). [Figure 54] Kurumi was influenced by the “cute kids”[179] popularized by American and British illustrators of children’s and women’s books, magazines, and ephemera in the early 1900s: Grace Drayton’s Campbell Soup Kids and Dolly Dimples, Rose O’Neill’s Kewpie [Figure 55]—which became widely counterfeited in Japan in the 1920s—and Mabel Lucie Attwell.[180] Kurumi’s formal attributes changed drastically over the decades,[181] from a “roughly four heads tall” preadolescent girl in the manga’s early episodes to “an extremely stylized character no more than two heads high, and of unknown age”[182] by the 1950s. [Figure 56] Alongside other artistic, social, and historical contexts underlying the shift, Kurumi’s evolution may reflect the iconic, stylized, kyara-like look[183] that emerged after World War II, for instance, in characters like the popular Tetsuwan Atomu (or Astro Boy, in the English translation).

Matsumoto’s comics impacted the development of Japanese cuteness, notably, when they diverged from the style of jojō-ga (“lyrical drawing”) developed by prominent modern painters and designers like Takehisa Yumeji, [Figure 57] Nakahara Jun’ichi, [Figure 58] or Kashō Takabatake, that dominated Japanese girls’ and women’s magazine covers and illustrations during the interwar era.[184] Unlike the lively characters in Matsumoto’s manga,[185] jojō-ga was lyrical and romantic, decadent and sentimental, with a taste for affluent beauties with big, melancholic eyes.[186] These “Yumeji beauties” (as they became known, after Takehisa Yumeji’s art) became the archetype for the slender heroines of post-war shōjo manga. In particular, Nakahara “depicted girls with big wet eyes and long eyelashes as opposed to the traditional hikime-kagibana concept of facial beauty,”[187] which featured slit eyes and hook noses (present, for instance, in Edo-period woodblock prints and paintings). As manga artist Hanamura Eiko puts it, Nakahara’s Westernized girl characters, resulting from a cocktail of influences from global and domestic sources including art deco, silent film-era Hollywood actresses, and the Japanese all-female musical theater troupe Takarazuka Revue, introduced cuteness to an element of “no-nationality… as it wasn’t clear which country they were from.”[188]

Figure 57 Takehisa Yumeji, Mandorinu (Girl with a mandolin), published in Shōwa mid-term era (1949-1970) by Unsodo. Japanese woodblock print, 22.50 cm x 14.50 cm. Source.

Figure 58 Cover of the girls’ magazine Shōjo no Tomo from 1937, featuring an illustration by Nakahara Jun’ichi. Source.

Figure 59 Pages from Takahashi Macoto’s Sakura Namiki (1957), with innovative “introspective” panels. Source.

Jojō-ga artists also illustrated Class S literature, i.e., stories about romantic friendships between girls, like Yoshiya Nobuko’s Hana Monogatari (“Tales of Flowers,” 1916-1924) or Kawabata Yasunari and Nakazato Tsuneko’s Otome no Minato (“Port of Maidens,” 1938).[189] Takahashi Macoto continued the jojō-ga tradition in the post-war, mostly in illustrations and covers,[190] but also in shōjo manga like Sakura Namiki (“Rows of Cherry Trees,” 1957) and Tokyo-Paris (1959), which introduced innovative panel and page layouts oriented towards the expression of feelings and atmospheres.[191] [Figure 59] Takahashi’s drawings of starry-eyed foreign princesses were influential in the creation of lolita fashion,[192] and have enjoyed continued popularity among its practitioners.[193] [Figure 60] Takahashi, along with female authors like Nishitani Yoshiko (Mary Lou, 1965), Hanamura Eiko (Kiri no Naka no Shōjo, “Girl in the Fog,” 1968), Hideko Mizuno (Fire!, 1969–1971, the first girls’ manga with a male protagonist and a sex scene), and Maki Miyako—who also created Japan’s famous Barbie-like doll, Licca-chan, in 1967 [Figure 61]—were instrumental in developing shōjo manga visually, narratively, and thematically throughout the 1960s. Drawing from Masubuchi Sōichi’s Kawaii Shokogun (“Cute Syndrome,” 1994), Shiokawa Kanako explains that:

“The most significant feature of this particular art style in the late sixties was the overwhelmingly large eyes of just about all the characters, many taking up nearly half of the faces…. Specifically (and often derisively) known as shōjo manga eyes, characters in such girls’ comics had huge eyes made of enormous, dilated orbs of black pupils filled with numerous stars, sparkles, and glittering dots… These large-eyed girls were always accompanied by highly stylized drawings of blooming flowers that crowded the background. These flowers were so abundant and so consistent in girls’ comics that their presence became the signature feature, an icon, of the girls’ comics style.”

Shiokawa also notes the “nearly complete avoidance of secondary sexual features, especially breasts”[195] during this period, that kept heroines in safe girl‑child territory and assured they were cute girls instead of beautiful, grown-up women.

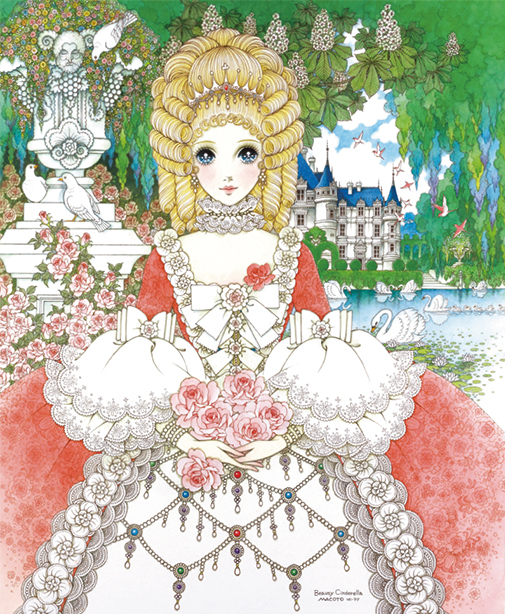

Figure 60 (left) Example of a foreign princess illustration by Takahashi Macoto. Source.

Figure 61 (right) A Licca-chan doll from the late 1960s. Source.

Figure 62 Tezuka Osamu’s Tetsuwan Atomu, or Astro Boy, the first anime television series. Source.

Figure 63 The kawaii character Doraemon, from Fujiko Fujio’s eponymous best-selling comedy manga. In the footsteps of Norakuro and Tank Tankuro, Doraemon is an animal-shaped robot from the future. Source.

In the postwar period, kodomo manga (children’s comics) continued to prosper, with characters in the tradition of interwar children’s mascots like Norakuro and Tank Tankuro. The unavoidable reference is Tezuka Osamu (1928-89), the author whose centrality to the postwar manga and anime canon and industry earned him the monikers “father of manga,” “god of manga,” or “the Walt Disney of Japan.”[196] Tezuka is the author of cute characters which have raised to the status of Japanese national mascots, such as Leo and Tetsuwan Atomu—known, in the West, as Kimba the White Lion and Astro Boy, respectively, a lion cub and a boy robot. The latter was also the first anime television series, produced by Tezuka’s animation studio Mushi Production and aired from 1963 to 1966. [Figure 62] Although Tezuka dabbled in shōjo manga with Ribbon no Kishi (Princess Knight, 1953-56), a fantasy adventure following in the footsteps of Nazo no Clover’s tomboy (otenba) heroine, Tezuka’s main contribution to kawaii culture was his borrowing of Disneyesque cuteness to create kyara, i.e., a very stylized character, often with cute features and proportions.[197] As noted by scholar Marco Pellitteri, although Tezukian kyara were kawaii, they were often “involved in stories where their substance is not abstract but solid, vulnerable, and at times mortal.”[198] However, in the case of later kyara that took inspiration from Tezuka, like the beloved robotic cat Doraemon, [Figure 63] the body of the cute mascot typically becomes “dehumanized and superhumanized, abstract and inanimate,”[199] and thus no longer subject to vulnerability and death.

Figure 64 The lively orphan Candice Adley from Candy Candy, by Nagita Keiko (story) under the pen name and Igarashi Yumiko (art). Source.

In the 1970s, authors like Igarashi Yumiko (Candy Candy, 1975-79) or Yamato Waki (Haikara-san ga Tōru, 1975-77, Asakiyumemishi, 1979) helped revitalize the shōjo demographic with strong female leads, while sticking to traditional themes (e.g., heart-warming stories about orphans). [Figure 64] Moreover, the 1970s cemented an influential trope that contrasted ordinary cute heroines with the more mature‑looking, utsukushii (“beautiful”) nemesis. Shiokawa exemplifies the cute vs. beauty trope, for instance, by comparing Marie Antoinette, the protagonist of Ikeda Ryoko’s manga hit Versailles no Bara (The Rose of Versailles, 1972-73), with her nemesis, Madame Du Barry. As she puts it,

“This particular formula implicitly leaves a message that being ‘cute’ is a virtue and, in an oddly paradoxical way, strength. However, cuteness in this instance is not in direct opposition to ugliness or neatness. It is clear by the characteristics of the heroine’s nemesis that cuteness in the girls’ comics convention battles against “beauty,” that is, perfection and maturity… Masubuchi argues that physical beauty is a fatefully determined state of perfection, unlike the states indicated by such expressions as kirei (pretty, neat), suteki (dashing), or kakko ii (cool, good‑looking)… In other words, even conventionally ‘ugly’ or ‘plain’ persons, as many girls’ comics heroines are supposed to be, can make themselves ‘cute’ by working hard at it.”

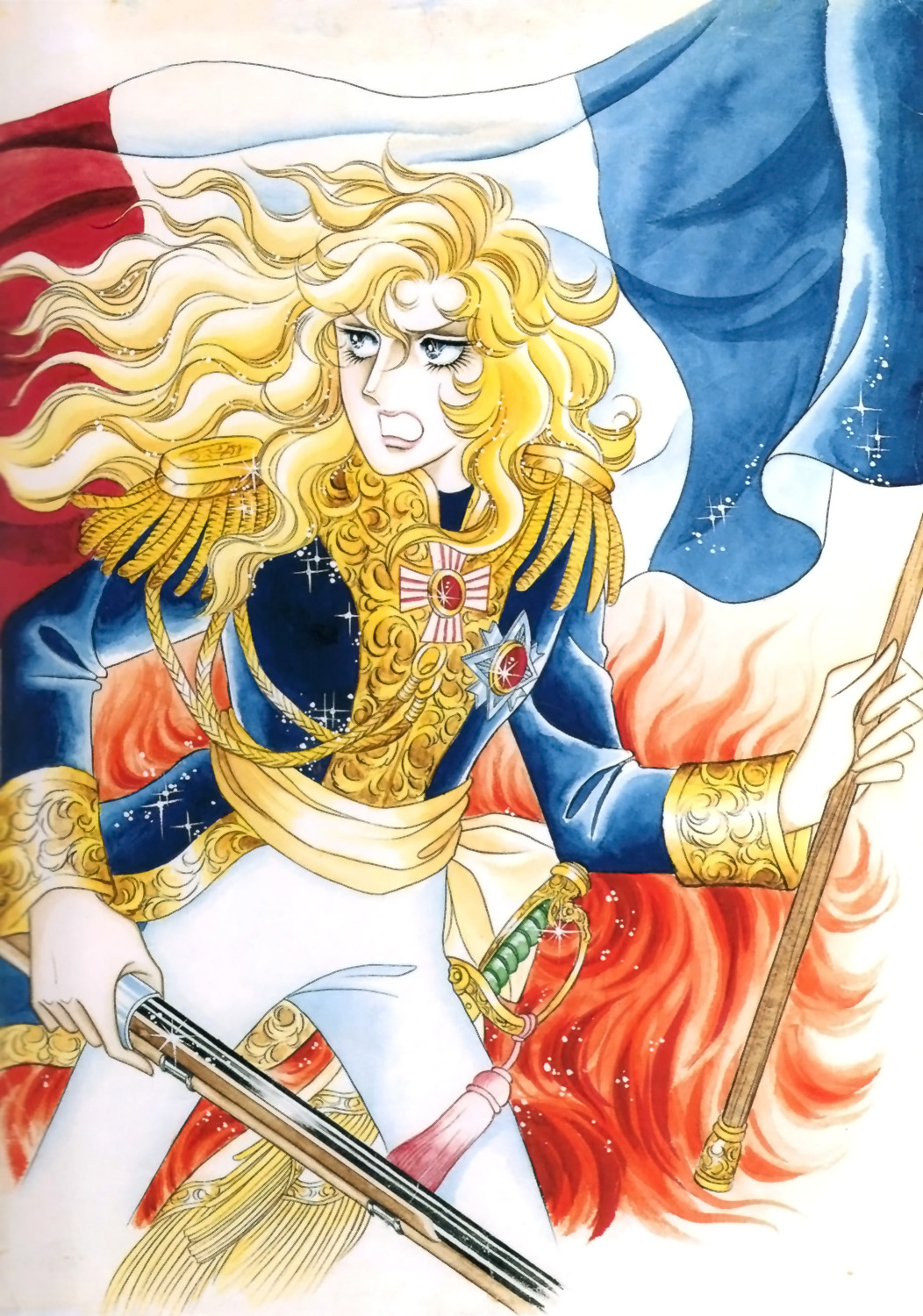

Figure 65 Lady Oscar, a supporting character from Ikeda Ryoko’s The Rose of Versailles, who stole Marie Antoinette’s protagonist and became one of the most iconic characters in shōjo manga. Source.

Ikeda Ryoko is part of the Year 24 Group (Nijūyo-nen Gumi), a group of female manga artists that revolutionized the shōjo genre in the 1970s. Along with Ikeda, authors such as Hagio Moto (Thomas no Shinzō, The Heart of Thomas, 1974-75), Takemiya Keiko (Kaze to Ki no Uta, “Ballad of the Wind and the Trees,” 1976-84), or Aoike Yasuko’s Eroica Yori Ai wo Komete (From Eroica With Love, 1976-2012),[201] changed the form and content of Japanese girls’ comics. As well, their work rehabilitated the genre in the eyes of the critics and a broader crowd (beyond the target audience of teenage girls), that up to that point had generally held a negative view on girls’ comics.[202] The Year 24 Group breathed a new depth and expanded the scope of what cuteness can express. Ikeda’s Versailles no Bara, for instance, experimented with gender and class roles and introduced a political flavor into the love narrative, namely, with the iconic character of Lady Oscar, an androgynous female lead who joins the French Revolution. [Figure 65] In turn, Hagio and Takemiya pioneered the shōnen-ai genre in manga with stories about same-sex love between bishōnen, i.e., doe-eyed “pretty boys” with angelic faces and androgynous bodies. Thomas no Shinzō and Kaze to Ki no Uta are both dark, existential stories set in “exotic,” decidedly non-Japanese backgrounds, namely, nineteenth-century European Catholic boarding schools, dealing with difficult topics like suicide, sexual abuse, racism, homophobia, and pedophilia. [Figures 66 & 67]

Figure 66 Page from Hagio Moto’s Thomas no Shinzō, showcasing protagonist Erich von Fruhling in a flowy, emotional panel layout. Moto Hagio, The Heart of Thomas, trans. Rachel “Matt” Thorn (Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics Books, 2013), 351.

Figure 67 Cover of Takemiya Keiko’s Kaze to Ki no Uta, with protagonists Gilbert Cocteau (below, depicted as a fallen angel) and Serge Battour (above). Source.

Figure 68 Illustration by Ozaki Minami for her series Zetsuai 1989, featuring protagonist Nanjo Koji. Source.

In the 1980s, the majority of bishōnen characters morphed from Hagio and Takemiya’s genderless cherubs to incorporate more masculine features, already found in the characters of Oscar and Andre from Ikeda’s The Rose of Versailles or Dorian and Klaus from Aoike’s From Eroica with Love. Bishōnen characters also became associated with the rise of the dōjinshi (“self-published” or “niche” magazines) or amateur manga movement and girls’ comics magazines (e.g., June) that published tanbi (“aesthetic”) gay erotica “fusing together beauty, romance, and eroticism, along with a dash of decadence.”[203] In amateur manga, female fans began to self-publish pornographic parodies of their favorite (male-oriented) shows, such as Captain Tsubasa, Uchū Senkan Yamato (Space Battleship Yamato), or Saint Seiya, where they “liked to do silly things with manly male characters, like putting them in ballet tunics or giving them kitty ears,” or even “put the manly males in bed together.”[204] The self-deprecating term yaoi—an acronym of yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi, meaning “no climax, no point, no meaning”—emerged to describe these plotless gay dramedies or over-the-top melodramas. Yaoi characters from the 1980s and 1990s were often bishōnen with elongated faces, pointy chins, wide and sparkly rectangular eyes, flowy hair, and slender bodies with long legs and well-developed torsos. In Ozaki Minami’s iconic Zetsuai 1989 (1989-91), that started as a Captain Tsubasa fanzine before transitioning to commercial publication, the characters are so stylized that at times they look more like alien creatures than men. [Figure 68]

Figure 69 Illustration from Nakamura Shungiku’s Junjō Romantica with markers of cuteness: pink colors, flowers, a teddy bear, big-eyes, blushing. Source.

Figure 70 Nanase Haruka, the protagonist of the sports anime series Free! Iwatobi Swim Club, 2013. Source: Free! Eternal Summer, episodes 13, “Hajimari no Eternal Summer!,” directed by Utsumi Hiroko, written by Yokotani Masahiro, and produced by Kyoto Animation, aired September 24, 2014, on Tokyo MX, TVA, ABC, BS11, AT-X, NHK G Tottori (GIF via).

While tanbi was never entirely divorced from the kawaii, the late 1990s and 2000s brought back a cuter sensibility to boys’ love or BL (the dominant term for this genre today). Popular series like Nakamura Shungiku’s Junjō Romantica (Pure Romance, since 2003) or Sekai-Ichi Hatsukoi (“The World’s Greatest First Love,” since 2006) retain tanbi elements but are populated with chibi “cute caricatures,” adorable animal mascots, round-eyed blushing boys, and lots of pink in covers and illustrations. [Figure 69] Contemporary bishōnen designs, both in yaoi and “regular” (heterosexual) shōjo manga like Fruits Basket (1998-2006) or Ōran Kōkō Host Club (Ouran High School Host Club, 2002-10), tend to have slighter body frames, larger heads with delicate jawlines and necks, and bigger eyes than the majority of their 1980s and early 1990s predecessors (e.g. Sailor Moon’s Tuxedo Mask or Mars’ Rei Kashino). Anime also contributed to the cutification of characters, as television adaptations of manga tended to make characters rounder and more standardized (see, for instance, the difference between the Sailor Moon manga and its 1990s anime adaptation). More recent titles like Free! or Yuri!!! on Ice draw on this “cute continuum” to deliver sports anime (swimming and figure skating, respectively) catering to female audiences with “passionate friendships” between male protagonists and fanservice for women. [Figure 70]

Figure 71 Rumiko Takahashi’s perky, bikini-wearing alien princess Lum (center), from the romantic sci-fi comedy Urusei Yatsura. Source.

Figure 72 Nausicaä, the princess of the Valley of the Wind, in Miyazaki Hayao’s eponymous anime film, from 1984. Source: Kaze no Tani no Nausicaä, directed by Miyazaki Hayao, Tokyo: Studio Ghibli, Inc. (GIF via).

Cuteness played an equally crucial role in the development of boys’ comics, or shōnen manga. During the 1970s and 1980s, many heroines in shōnen manga morphed into what Japanese psychologist Saitō Tamaki calls the sento bishōjo or “beautiful fighting girl.”[205] This new breed of cute female character was perky with a childlike face, and wore increasingly revealing outfits “that emphasized their smallish but well-developed breasts.”[206] [Figure 71] She was also powerful enough to fight alongside male heroes, or become the protagonist herself. [Figure 72] These characteristics distinguished the sento bishōjo from the virtuous madonnas and passive sidekicks abounding thus far,[207] fluctuating between empowerment and sexual objectification in a challenge to “easy categorization as either (or simply) a feminist or sexist script.”[208] Indeed, one of the most iconic sento bishōjo, appearing in the Daicon IV Opening Animation—a 6-minute anime made for the 1983 Nihon SF Taikai convention in Osaka, by an amateur group that went on to form the influential animation studio Gainax—is a cute girl in a Playboy bunny outfit, who singlehandedly fights an endless array of famous sci-fi and fantasy characters while air surfing in a magical sword. [Video 7] Moreover, the sento bishōjo spread across male and female demographics, from Miyazaki Hayao’s animated feature films (e.g., Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind) to magical girl animanga like Takahashi Rumiko’s Urusei Yatsura, Nagai Gō’s Cutie Honey, or Takeuchi Naoko’s Sailor Moon.

Video 7 (left) Daicon IV Opening Animation, 1983. The first minute is a summary of the previous Daicon III Opening Animation, made by the same team in 1981. Source.

Figure 73 Example of a pornographic lolicon illustration with “perverse” techno-fetishist elements in Manga Burikko, November 1983 (censored). Source.

The sento bishōjo contributed to the appearance of lolicon during the early 1980s, in specialized comics magazines like Lemon People or Manga Burikko, as well as dōjinshi and home video animations. Lolicon, from “Lolita complex,” is a genre of pornographic manga, anime, or videogames in which underage characters engage in sexual acts, ranging from soft eroticism to violent or “perverse” (hentai) scenarios, often with techno-fetishist elements.[209] [Figure 73] While aimed at a male adult audience, lolicon magazines in the 1980s often featured the work of female shōjo manga artists, male artists mimicking the style of girls’ comics, or other forms of cuteness.[210] In fact, “the first blatantly lolicon work in Japan”[211] was published in 1979 by the “father of lolicon,” Azuma Hideo, in a contribution to the manga fanzine Cybele that featured erotic depictions of kawaii Tezuka-style characters. Other heroines, like Miyazaki’s sento bishōjo or magical girls like Minky Momo, became lolicon icons portrayed by fans in erotic and pornographic amateur manga. As scholar Shigematsu Setsu suggests, in lolicon manga, “it is not the age of the girl that is attractive, but a form of ‘cuteness’ (kawaii‑rashii) that she represents.”[212] In this same vein, Patrick Galbraith argues that lolicon cannot be reduced to a male power fantasy, as its imagery is diverse in terms of style, content, reception, and its place in the broader crossgender flows at play in Japanese comics.[213]

Figure 74 Cover and back cover of volume 5 of the moé manga series Shūkan Watashi no Onii-chan (Weekly Dearest My Brother), running from 2003 to 2004, by Vv.Aa. Although mostly innocent-looking, there the series contains soft lolicon elements. Each issue was accompanied by a figure by the celebrated Japanese toy designer Ohshima Yuki. Source.

Figure 75 Cover of the iconic moé manga series Yotsuba&!, by Azuma Kiyohiko. Source.

In 1989, the incident of serial killer Miyazaki Tsutomu, the “otaku murderer,” who killed several children, originated a nation-wide debate on obscenity that targeted “hazardous comics” and the anime and manga superfans known as otaku (a term roughly equivalent to “nerd” or “geek” in the West). In the early 1990s, the police raided bookstores selling dōjinshi and filled obscenity charges against authors, and large-scale self-publishing events, like the Comic Market (or Comiket)—Japan’s largest fan convention, mostly dedicated to amateur manga—were put under scrutiny by the authorities.[214] While the infatuation with bishōjo characters did not waver and was reignited by the success of series like Shinseiki Evangelion (Neon Genesis Evangelion) and Tokimeki Memorial, a new trend in male-oriented manga and anime rose in popularity that remains strong to this day: moé. Moé replaced the explicit sexuality in lolicon by feelings of tenderness and rooting for characters that fit “little sister” (imōto) or “daughter” (musume) types, sometimes round and adorable to the point of blobishness, known as a loli. The origins of moé overlap with the lolicon tradition, wavering between or combing, as Murakami Takashi puts it, “an innocent fantasy” and “distorted sexual desires.”[215] [Figure 74] However, other series within the moé anime and manga genre, like the iconic Yotsuba&! by Azuma Kiyohiko, present wholesome slice of life comedies, in which cuteness is the central affect in sophisticated storytelling and artwork. [Figure 75] For a more in-depth analysis of moé, read the encyclopedia entries “It Girl” and “CGDCT,” or the paper “She’s Not Your Waifu; She’s an Eldritch Abomination.”

ABSOLUTE BOYFRIEND ; (BETAMALE) ; CGDCT ; CREEPYPASTA ; DARK WEB BAKE SALE ; END, THE ; FAIRIES ; FLOATING DAKIMAKURA ; GAIJIN MANGAKA ; GAKKOGURASHI ; GESAMPTCUTEWERK; GRIMES, NOKIA, YOLANDI ; HAMSTER ; HIRO UNIVERSE ; IKA-TAKO VIRUS ; IT GIRL ; METAMORPHOSIS ; NOTHING THAT’S REALLY THERE; PARADOG ; PASTEL TURN ; POISON GIRLS ; POPPY ; RED TOAD TUMBLR POST ; SHE’S NOT YOUR WAIFU, SHE’S AN ELDRITCH ABOMINATION ; ZOMBIEFLAT